Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in a language that can distinguish one word from another. These subtle yet powerful elements serve as the foundation for spoken communication, allowing us to differentiate between words like “bat” and “pat,” despite their similar structures. By mastering the phonetic components of language, we gain a deeper understanding of pronunciation, accents, and the complexities of human speech. Whether you’re a linguist, language learner, or simply curious about how we communicate, exploring phonemes offers valuable insights into the mechanics of language and the way we perceive sound.

Types of phonemes:

Phonemes are the smallest units of sound that distinguish words in a language. They can be categorized into two main types: vowels and consonants.

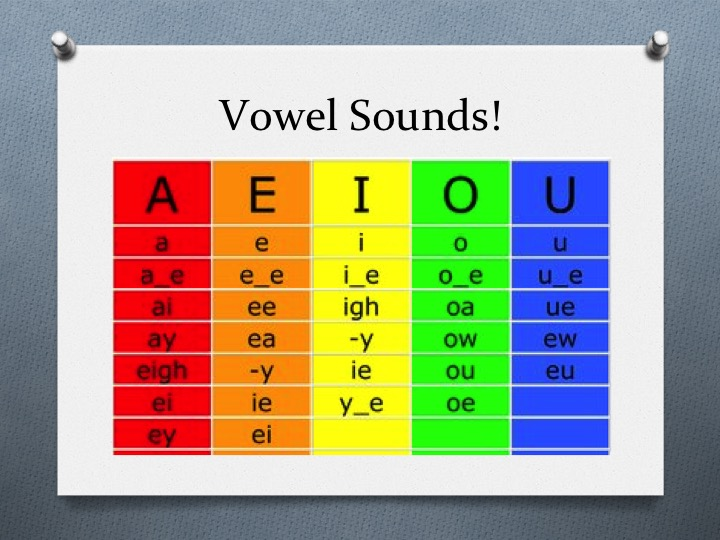

Vowel Phonemes (20):

Vowel phonemes are distinct sound units in a language that are produced without any significant constriction or closure in the vocal tract, allowing the airflow to pass through smoothly. These sounds are central to the syllables in words, and in English, there are generally around 20 vowel phonemes, depending on the accent.\

Vowel A Sounds:

The English language has several vowel sounds that can be represented by the letter “A.” These sounds vary depending on the word and the context in which the letter “A” is used. Below are the primary vowel sounds associated with the letter “A” in English, along with examples: The letter “A” in English can represent a variety of sounds depending on the word and accent. The primary sounds include:

1./æ/ – Short A Sound

- This sound is commonly referred to as the “short A.” It is found in many words where the letter “A” is followed by a consonant in a stressed syllable.

- Examples:

- Cat /kæt/

- Apple /ˈæpəl/

- Mat /mæt/

2./eɪ/ – Long A Sound

- The “long A” sound is typically represented by the combination of “a” and a silent “e” at the end of the word, or by other letter combinations like “ai” or “ay.”

- Examples:

- Cake /keɪk/

- Day /deɪ/

- Rain /reɪn/

3. /ɑː/ – Broad A or Open A Sound

- This sound is often found in words where “A” is followed by an “r” or in certain dialects, particularly British English.

- Examples:

- Father /ˈfɑːðər/

- Car /kɑːr/ (in some accents)

- Calm /kɑːm/

4./ɔː/ – Rounded A Sound

- In some accents, particularly British English, the “A” in certain words can have a rounded vowel sound similar to “aw.”

- Examples:

- All /ɔːl/

- Talk /tɔːk/

- Water /ˈwɔːtə/

5. /æ/ – Nasalized A Sound

- In some regional accents, particularly in American English, “A” before nasal consonants like “n” or “m” can be nasalized.

- Examples:

- Man /mæn/

- Hand /hænd/

- Sand /sænd/

6. /ə/ – Schwa Sound

- The schwa sound is an unstressed and neutral vowel sound. The letter “A” can represent the schwa sound in unstressed syllables.

- Examples:

- About /əˈbaʊt/

- Alone /əˈloʊn/

- Around /əˈraʊnd/

7. /e/ – Short E Sound (in certain dialects)

- In some dialects, particularly in Northern England, the “A” in some words is pronounced similarly to the short “E” sound.

- Examples:

- Many /ˈmɛni/

- Any /ˈɛni/

8./ɒ/ – Short O Sound (in certain words)

- In some British accents, the “A” in words like “what” or “was” can be pronounced with a short “O” sound.

- Examples:

- What /wɒt/

- Was /wɒz/

Vowel E Sounds

1./ɛ/ – Short E Sound

- This is the typical sound of the letter “E” in many words.

- Examples:

- Bed /bɛd/

- Red /rɛd/

- Let /lɛt/

2./iː/ – Long E Sound

- This sound often occurs when “E” is followed by a silent “E” or in certain vowel combinations like “ee” or “ea.”

- Examples:

- See /siː/

- Me /miː/

- Heat /hiːt/

3./ə/ – Schwa Sound

- The letter “E” can represent the schwa sound, especially in unstressed syllables.

- Examples:

- Taken /ˈteɪkən/

- Water /ˈwɔːtər/

- Silent /ˈsaɪlənt/

4./ɪ/ – Short I Sound (in some dialects)

- In some dialects or contexts, “E” can be pronounced like a short “I” sound.

- Examples:

- Pretty /ˈprɪti/

- England /ˈɪŋɡlənd/

5./eɪ/ – Diphthong E Sound

- Sometimes, “E” is part of a diphthong, creating a sound that transitions between two vowel sounds.

- Examples:

- They /ðeɪ/

- Sleigh /sleɪ/

Vowel I Sounds:

In English, the letter “I” can represent several different vowel sounds, depending on the word and its context. Below is a breakdown of the primary sounds associated with the letter “I,” along with examples for each.

1. /ɪ/ – Short I Sound

Milk /mɪlk/

This is the most common sound associated with the letter “I” in English. It is typically a short, clipped sound.

Examples:

Sit /sɪt/

Bit /bɪt/

2. /aɪ/ – Long I Sound (Diphthong)

- This sound is a diphthong, meaning it starts with one vowel sound and glides into another. It typically appears in words where “I” is followed by a consonant and a silent “E,” or in some other cases like “I” at the end of a syllable.

- Examples:

- Time /taɪm/

- Mine /maɪn/

- Sky /skaɪ/

3./iː/ – Long E Sound

- In some words, the letter “I” is pronounced with a long “E” sound, especially in loanwords from other languages or in certain syllables.

- Examples:

- Machine /məˈʃiːn/

- Police /pəˈliːs/

- Unique /juˈniːk/

4./ɜː/ – R-colored Vowel (In Some Dialects)

- In certain dialects, particularly in American English, the letter “I” before an “R” can produce an R-colored vowel sound.

- Examples:

- Bird /bɜːrd/

- Stir /stɜːr/

- First /fɜːrst/

5. /ɪə/ – Diphthong I Sound (In Some Dialects)

- In some British accents, “I” can be pronounced as a diphthong, transitioning from a short “I” sound to a schwa.

- Examples:

- Idea /aɪˈdɪə/

- Near /nɪə/

- Fear /fɪə/

Vowel o Sounds:

The letter “O” in English represents several different vowel sounds, which vary depending on the word and context. Here’s a breakdown of the primary sounds associated with the letter “O,” along with examples for each.

1. /ɒ/ – Short O Sound

- This sound is common in British English and some American accents. It is a short, rounded sound, often heard in words where “O” is followed by a consonant.

- Examples:

- Hot /hɒt/

- Pot /pɒt/

- Rock /rɒk/

2. /oʊ/ – Long O Sound (Diphthong)

- This is a diphthong, meaning the sound starts with an “o” sound and glides into a “u” sound. It is common in American English.

- Examples:

- Go /ɡoʊ/

- Home /hoʊm/

- Bone /boʊn/

3. /ɔː/ – Broad O Sound

- This sound is typical in British English, especially in words like “law” or “thought.” It is a long, rounded sound.

- Examples:

- Law /lɔː/

- Thought /θɔːt/

- Caught /kɔːt/

4. /ə/ – Schwa Sound

- The letter “O” can also represent the schwa sound in unstressed syllables. The schwa is the most common vowel sound in English and is pronounced with a relaxed tongue in the center of the mouth.

- Examples:

- Sofa /ˈsoʊfə/

- Today /təˈdeɪ/

- Doctor /ˈdɒktər/

5. /ʌ/ – Short U Sound

- In some words, particularly in American English, the letter “O” can be pronounced as a short “U” sound. This sound is often heard in words where “O” is followed by certain consonants.

- Examples:

- Love /lʌv/

- Some /sʌm/

- Above /əˈbʌv/

6. /uː/ – Long OO Sound

- In some cases, especially before certain consonant clusters or when combined with other vowels, “O” can be pronounced as a long “OO” sound.

- Examples:

- Lose /luːz/

- Move /muːv/

- Prove /pruːv/

7. /ɔɪ/ – OY Sound (Diphthong)

- In words where “O” combines with “I,” it can produce the “OY” diphthong, which starts with the “O” sound and glides into a “Y” sound.

- Examples:

- Boy /bɔɪ/

- Toy /tɔɪ/

- Joy /dʒɔɪ/

8. /ʊ/ – Short OO Sound

- In some cases, especially in certain words where “O” is followed by “O” or “U,” the sound is pronounced as a short “OO” sound.

- Examples:

- Good /ɡʊd/

- Foot /fʊt/

- Wolf /wʊlf/

Vowel U Sounds:

The letter “U” in English represents several distinct vowel sounds, which vary depending on the word and context. Here’s a breakdown of the primary sounds associated with the letter “U,” along with examples for each:

1. /ʌ/ – Short U Sound

- This is a common sound associated with the letter “U,” especially in stressed syllables. It is a short, relaxed sound, similar to the vowel in “cup.”

- Examples:

- Cup /kʌp/

- Bus /bʌs/

- Luck /lʌk/

2. /juː/ – Long U Sound (Diphthong)

- This sound occurs when “U” is pronounced as a combination of a “Y” sound followed by a long “U” sound. It often appears at the beginning of words or after certain consonants.

- Examples:

- Use /juːz/

- Cute /kjuːt/

- Music /ˈmjuːzɪk/

3. /uː/ – Long OO Sound

- The letter “U” can also represent a long “OO” sound, which is a pure vowel sound without the initial “Y” sound. This occurs especially in words where “U” follows certain consonants or is part of a vowel digraph.

- Examples:

- True /truː/

- Blue /bluː/

- Rude /ruːd/

4. /ʊ/ – Short OO Sound

- In some words, particularly before certain consonants or in unstressed syllables, “U” is pronounced as a short “OO” sound. This sound is similar to the vowel in “foot.”

- Examples:

- Put /pʊt/

- Good /ɡʊd/

- Bull /bʊl/

5. /ɪ/ – Short I Sound (In Certain Words)

- Occasionally, “U” can be pronounced as a short “I” sound, especially in unstressed syllables or in specific words of Latin origin.

- Examples:

- Busy /ˈbɪzi/

- Minute /ˈmɪnɪt/

- Business /ˈbɪznɪs/

6. /ə/ – Schwa Sound

- In unstressed syllables, the letter “U” can also be pronounced as a schwa, which is the most common vowel sound in English. The schwa is a neutral, relaxed sound.

- Examples:

- Support /səˈpɔːrt/

- Supply /səˈplaɪ/

- Circus /ˈsɜːrkəs/

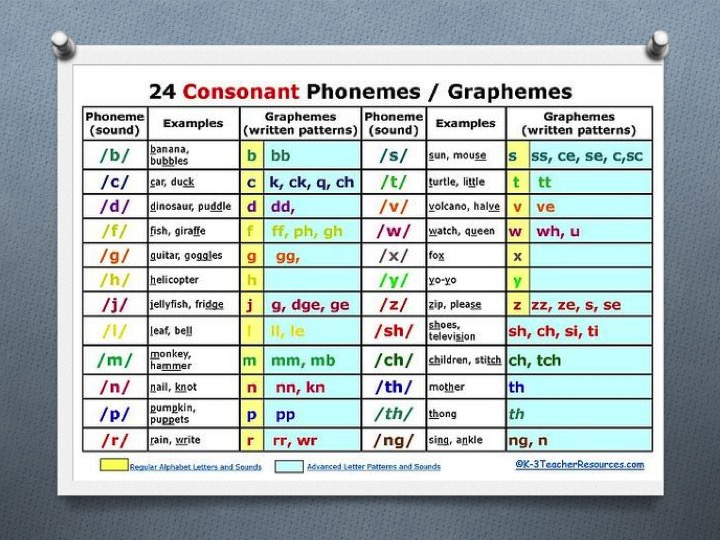

Consonant Phonemes (24):

Consonant phonemes are sounds produced by obstructing airflow in some way during articulation. English has 24 consonant phonemes, which can be further divided into voiced and voiceless phonemes, depending on whether the vocal cords vibrate during sound production.

Voiced Consonants:

- /b/: As in bat, the /b/ sound is produced by bringing the lips together and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /d/: As in dog, the /d/ sound is made by placing the tongue against the upper teeth ridge and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /g/: As in go, the /g/ sound involves the back of the tongue touching the soft palate while vibrating the vocal cords.

- /v/: As in van, the /v/ sound is produced by placing the upper teeth on the lower lip and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /ð/: As in this, the /ð/ sound is created by placing the tongue between the teeth and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /z/: As in zoo, the /z/ sound is made by placing the tongue against the teeth ridge and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /ʒ/: As in measure, the /ʒ/ sound is produced by bringing the tongue close to the teeth ridge and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /dʒ/: As in judge, the /dʒ/ sound involves the tongue touching the teeth ridge and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /m/: As in man, the /m/ sound is produced by closing the lips and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /n/: As in no, the /n/ sound is made by placing the tongue against the teeth ridge and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /ŋ/: As in sing, the /ŋ/ sound is produced by the back of the tongue touching the soft palate and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /l/: As in love, the /l/ sound is created by placing the tongue against the teeth ridge while allowing air to flow along the sides of the tongue.

- /r/: As in run, the /r/ sound is made by curling the tongue slightly and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /w/: As in wet, the /w/ sound is produced by rounding the lips and vibrating the vocal cords.

- /j/: As in yes, the /j/ sound involves raising the middle of the tongue close to the palate and vibrating the vocal cords.

Voiceless Consonants:

- /p/: As in pat, the /p/ sound is produced by bringing the lips together and releasing a burst of air without vibrating the vocal cords.

- /t/: As in top, the /t/ sound is made by placing the tongue against the teeth ridge and releasing a burst of air without vocal cord vibration.

- /k/: As in cat, the /k/ sound involves the back of the tongue touching the soft palate and releasing a burst of air without vibrating the vocal cords.

- /f/: As in fan, the /f/ sound is produced by placing the upper teeth on the lower lip and releasing air without vocal cord vibration.

- /θ/: As in think, the /θ/ sound is created by placing the tongue between the teeth and releasing air without vibrating the vocal cords.

- /s/: As in snake, the /s/ sound is made by placing the tongue against the teeth ridge and releasing air without vocal cord vibration.

- /ʃ/: As in ship, the /ʃ/ sound is produced by bringing the tongue close to the teeth ridge and releasing air without vibrating the vocal cords.

- /tʃ/: As in church, the /tʃ/ sound involves the tongue touching the teeth ridge and releasing air without vocal cord vibration.

Short Vowels Can Be Spelled in Four Ways:

- The most common way: a single vowel in a closed syllable usually says a short sound.

(In a closed syllable, a single vowel is followed by a consonant.)- In the word cat, A is followed by T and says /ă/.

- In the word pet, E is followed by T and says /ĕ/.

- In the word dish, I is followed by SH and says /ĭ/.

- In the word mob, O is followed by B and says /ŏ/.

- In the word tub, U is followed by B and says /ŭ/.

- Vowel teams can make short vowel sounds.

(In a vowel team, two vowels work together to make one sound.)- EA can say /ĕ/ as in bread and sweat.

- OU can say /ŭ/ as in touch and young.

- Single vowels can say the short sound of other vowels.

- A after W can say /ŏ/ as in water and want.

- Y in a closed syllable says /ĭ/ as in gym and myth.

- O can say /ŭ/ as in love and oven.

- A vowel can make the short U or short I sound in an unaccented syllable.

(A schwa is a muffled vowel sound heard in an unaccented syllable in many English words.)- A can say /ŭ/ as in about.

- E can say /ĭ/ as in enemy.

- I can say /ŭ/ as in family.

- O can say /ŭ/ as in bottom.

- U can say /ĭ/ as in minute.

- Y can say /ŭ/ as in syringe.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, phonemes are the fundamental building blocks of spoken language, representing the smallest units of sound that can differentiate meaning in words. Understanding and analyzing phonemes is crucial for various fields, including linguistics, language teaching, and speech therapy, as it helps in recognizing how sounds function within a language. The study of phonemes enhances our ability to comprehend pronunciation patterns, dialectal variations, and language development. Ultimately, phonemes form the foundation for effective communication, enabling us to convey and interpret meaning through speech.